CHINA TRAINS SIGHTS ON THAILAND

China and Japan vie for hearts, minds and markets in Thailand and beyond

by Philip Cunningham

In 1981, Malaysia’s PM Mohamad Mahathir launched a campaign for “Asian values,” citing “diffidence” as one of the characteristics that ostensibly made Asians different, though he did so in a haughty, attention-grabbing kind of way. More successful was his “Look East Policy.” As decades of diplomacy subsequently made clear, it was Japan that Mahathir had in mind, with China and other countries in the "East" hovering slightly out of focus in the background.

Japan to this day enjoys a reputation for behavior that is “Asian,” in the Mahathir sense of the word, in that it adheres to norms of self-effacement, politesse, and indeed, diffidence, Meanwhile China, full of swagger, self-promotion and dreams of conquest, has chosen, at least since the time its economy really started to bloom, to lead not from behind but way up front. The wolf warriors continue to howl.

The incongruous leadership styles in Japan and China go beyond cliché to the realm of policy. Different approaches can be seen as the two nations compete for hearts and minds in Thailand and other coveted markets, especially in the realm of infrastructure projects.

Tokyo’s soft-shoe disbursement of funds overseas has been fine-tuned over many decades to blend in with the local environment with the result that it is less showy and self-celebratory than Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road scheme. That’s not to say it’s flawless or free of intrigue, and indeed there are strings attached, though the goals and gains remain relatively modest.

In contrast, China’s recent efforts in the official development assistance game are in keeping with Xi’s grandiose visions of a “shared future for mankind.”

It’s arrogant, even for China.

To be fair, China’s unmerited self-confidence and self-regard in the game of foreign aid brings to mind the imperial strain of US foreign policy combined with the transactional bent of Donald Trump. As for Japan, which for a time embraced Mahathir’s vision of a world devoid of pesky Western values, it knows when to keep quiet.

For years Japan development aid was deaf to Western calls to take into account non-economic issues such as human rights and anti-democratic rule. A case in point is the way Japan blithely ignored sanctions and continued its unbridled “economic cooperation” with Beijing after the bloody June 4, 1989 crackdown at Tiananmen.

In the past twenty years or so, however, Japan’s rhetorical position has shifted to the point where it claims to be on board with best international aid practices, at least as defined by the US and Europe, while China increasingly remains the odd man out.

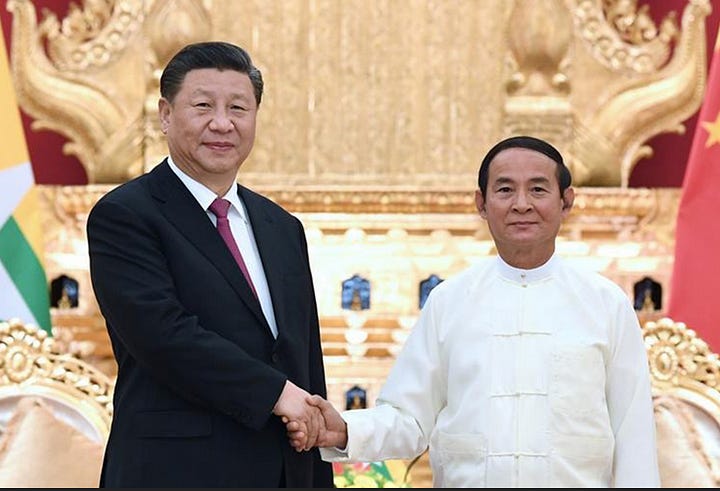

For example, China today stands almost alone in its unbridled support for the junta in Myanmar, despite worldwide sanctions in response to Naypyidaw’s dictatorial ravages. Well, not quite alone.

“End Japan’s loans to Myanmar’s Tatmadaw” pleads a recent article in the Bangkok Post, driving home the point that Japan and China may have more in common than it might appear at first glance.

From the amoral aid-giver’s point of view, domestic suffering and injustice, even war crimes, are best left unaddressed.

Tokyo plays a long game in the art of nurturing markets, and post 1989 China was one of those markets, though things didn’t exactly pan out as expected.

Long a recipient of Japanese aid, and no stranger to human rights abuse at home, Beijing’s promotion of the so-called “Belt and Road” now has it poised to be the lender of choice to rogue leaders, the first lender of last resort.

In return for China’s generosity come demands for adherence to a political line (on Taiwan first and foremost, but the list of cantankerous CCP talking points gets longer by the day)

Wanna be part of the Belt and Road?

No background check necessary, but if you don’t pay up, debt diplomacy is a force to be reckoned with. Default on ADB and the World Bank if you have to, but do pay China back.

Japan gets less press, but its low-profile and cautious approach arguably make it the more effective donor, inasmuch as it does not bite off more than it can chew.

That Japan should be deft, if not exactly diffident, in its foreign aid schemes is not entirely surprising given Tokyo’s long history of economic “cooperation,” including decades of tricky aid entanglement with China.

China’s top-down governance system, in contrast, leaves little room for China’s talented experts to ponder fine points and facts on the ground. There is little room to dwell on how the export of a megaproject impacts locals, and almost no recourse for those who disagree.

Sure, it’s clearly advantageous to Beijing to promote a rail line that cuts through the heart of Thailand to link China’s hinterland to the sea. Why not? Ditto for cutting a canal at the Kra Isthmus, or constructing a container train link from the Gulf of Siam to the Andaman.

But what’s in it for the locals, and what does it do to Thai sovereignty?

Ask Laos.

High speed rail makes sense in a nation with two large cities, but Thailand has only one.

Japan’s own research indicates that Thailand does not need, and will not necessarily benefit, from a fast train. It lacks the market conditions to repay the loans incurred, and anyway, what’s the rush, especially if the cargo is mostly Chinese and mostly containers?

Despite the shining legacy of the Shinkansen, and despite Japan’s vested interest in automobile exports, it prudently turned to funding smaller, more humble projects, such as subways and suburban rail lines. Japan, rightly proud of its bullet train (free of accident since it was built in 1964!) by all rights should be a contender for, if not the winner of, any bid to build a high speed train racing through Thailand.

The original and exemplary high-speed model, the Tokyo-Osaka run, has been profitable, and remains preferable to flying, because it links the downtowns of two mega-cities.

Ditto for China’s Beijing-Shanghai line, which is one of the few segments of China’s over-reaching high rail network that is actually turning a profit.

But not every market can bear the costs and disruption of a high-speed train.

As for the greater Bangkok area, light rail is a good fit.

The Japan-backed and implemented MRT Purple Line running from Bangkok to Nonthaburi is a case in point. The Purple Line, along with other incremental improvements in Thailands rail system move commuters away from the fray of a polluted city jammed with cars. Like the numerous Japan-Thai joint-venture bridges built across the Chao Phraya, inner-city rail is of no obvious service to Tokyo, but it serves Thailand well.

While Japan’s current aid policy is “cheap” in the sense it gives out loans instead of outright gifts, it is arguably offering much more for the money than China’s jacked-up high speed projects.

Japan official development assistance is mature, manageable, and relatively fine-tuned to regional needs, a stable symbiosis eight decades in the making.

Tokyo has worked tirelessly to burnish the bad optics of its naked aggresion during the Pacific War, and indeed, some of the aid in the early days was effectively a monetary apology for its war-time predations. But the militarists are long gone, replaced by mild-mannered corporate samurai. They seek to profit, albeit in gentler and generally agreeable terms.

China, on the other hand, long locked out of trade and aid to Thailand during the second half of the 20th century, was hemmed in by an assertive US foreign policy, but its isolation was also an own-goal committed by a “revolutionary” regime rooted in xenophobia.

In recent years, China has undergone a mad rush to make up for lost time, gaining impressive market share in trains, containers and automobiles in Thailand, enough to have Japan sweating bullets.

Beijing’s headstrong rush to conquer markets and reshape Asia in its image is a work in progress, but if the seemingly jinxed high speed rail project being pressed upon Thailand is anything to judge by, its brash vision may eventually be offset by delays, political bickering and economic loss.

Beijing’s failure to conduct adequate market research and due diligence, along with its concomitant willingness to ignore critics for the sake of national glory and political expediency, brings to mind not the diffident Japan of today, but the bad old bully days of the “Bridge over the River Kwai,” when human rights and political sovereignty took a back seat to imperatives for laying rail at a breakneck pace for geopolitical reasons that had nothing to do with the improving the quality of life of the host nation.